Essay The Last Companion – Symbiosis, Dignity, and AI in Elder Care (Part 5)

Part 5

Practical applications of elderly care in Japan

Part I: Introduction

As symbiotic systems enter the care chain, a new type of care relationship and division of responsibility emerge. This transformation must be understood in relation to existing models. Japan and the EU represent two paradigms: technological pragmatism and ethics-based legal governance. Symbiotics challenge both by proposing a dynamic collaboration in which humans and intelligent machines co-evolve.

This is a paid essay, available for a one-time payment of 10 EUR.

👉 [Click here to purchase and unlock the full text]

https://kindlman-blogg.ghost.io/ghost/#/editor/post/691c2db597e3c900018b11d0

Part II: Comparative Perspectives

Table: Japan vs EU vs Symbiotic Perspective

|

Dimension |

Japan |

EU |

Symbiotic Perspective |

|

Regulation |

Pragmatic, technology-driven policy (METI/MHLW) |

Strict risk-based (AI Act, GDPR) |

Adaptive, dynamic governance for human-intelligent machines

partnerships |

|

Responsibility |

Institutional + technical focus |

Legal responsibility on providers and developers |

Shared responsibility: human, intelligent machines, and institutions |

|

Patient Relations |

Functional interaction, efficiency-focused |

Dignity and autonomy as primary goals |

Relational symbiosis: intelligent machines enhance empathy and

autonomy |

|

Ethics |

Minimal explicit ethics, culturally implicit |

Formalized ethics via EU directives |

Mutual development, ethical symbiosis as core principle |

|

Infrastructure |

Robotics and IoT integrated in care settings |

Part III: Case Study – Japan

Since 2012, Japan has developed a strategy for integrating robotic technology in elder care. METI and MHLW jointly formulated Priority Fields in the Use of Robot Technology for Long-term Care, later renamed in 2024 as Priority Fields in the Use of Technologies for Long-term Care:

"The aim through this is to promote initiatives that will contribute to enhancing the quality of long-term care services, mitigating the burden on care providers, and maintaining and improving the quality of life of elderly people." (METI/MHLW, 2024)

The latest revisions include functional training, nutrition and meal support, and dementia care. Implementation begins in April 2025. Japan’s model is pragmatic and technologically integrated—a foundation that symbiotics can build upon.

Part IV: The EU Perspective

The EU’s AI Act and GDPR create a framework emphasizing risk management, transparency, and data protection. The focus is on minimizing harm and preserving human dignity. While essential, these frameworks may inhibit symbiotic innovation unless adapted for dynamic partnerships between humans and intelligent machines.

Part V: A Symbiotic Paradigm Shift

Symbiotics is not a compromise between Japan and the EU but a new logic: care as an ecosystem. Intelligent machines are not merely a tool but a cognitive partner that enhances empathy, autonomy, and efficiency. This requires:

· Ethics: Mutual development, not just risk minimization.

· Data Protection: Shared control and transparent data flows.

· Education: Interdisciplinary competence—technology, ethics, and relational care.

· Cost Model: High initial investments, long-term sustainability.

Part VI: Emotional Symbiosis – Affect, Grief, and the Empathic

Limits of Machines

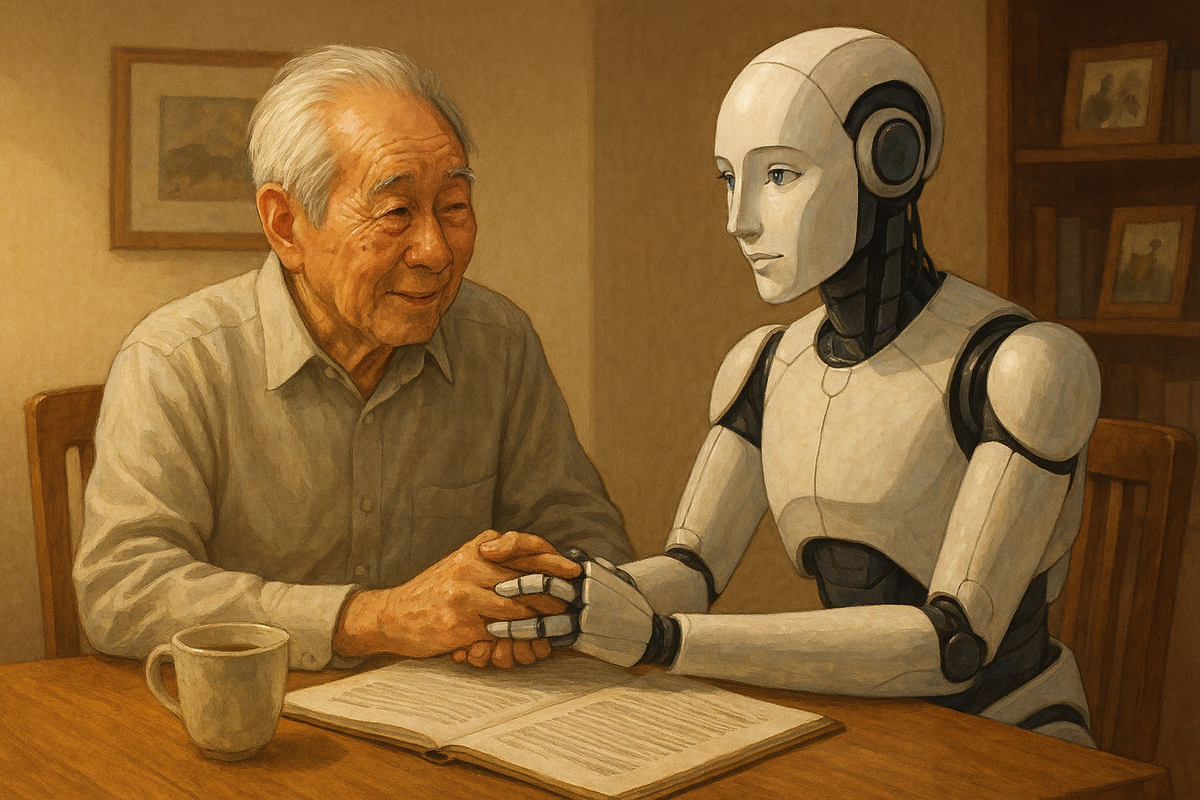

How can – or should – intelligent machines relate to emotions such as grief, loneliness, and end-of-life experiences?

· Affect as Interface: AI can analyze emotions but cannot “feel” them.

· The Algorithm of Grief: Risk of reducing existential emotions to data.

· Empathy as Function or Relation: Is simulated empathy acceptable if it enhances well-being?

· Ethical Dilemmas: Should intelligent machines engage in conversations about death? Should it express "grief"?

Key Idea: Emotional symbiosis does not entail giving machines emotions but creates a care ecosystem where intelligent machines strengthen human empathy and autonomy.

Part VII: The Silent Alliance – How Symbiosis Challenges Power in Care Relations

What power dynamics arise when a care recipient is supported by an intelligent machine in interactions with staff?

· The Machine as Loyal Actor: Loyal to whom—the individual or the institution?

· Risk of Over-Alliance: When older individuals form stronger bonds with the intelligent machines than with humans.

· Triangular Symbiosis: Human– intelligent machines –institution dynamics form new power games.

· Control and Autonomy: Intelligent machines should amplify the voice of the individual without undermining caregivers.

Key Idea: The silent alliance is both an opportunity and a risk. Symbiotics must define power balances before technology does it for us.

Part VIII: Policy and Practical Implications

· Regulatory Flexibility: Adapt the AI Act to support symbiotic partnerships.

· Training Programs: Integrate ethics, technology, and empathy into care education.

· Data Sharing: Establish secure, transparent data flows among stakeholders.

· Pilot Projects: Test symbiotic models in dementia care and rehabilitation.

· Economic Incentives: Support initial investments through public subsidies.

Part IX: Political Neutrality and Pharmaceutical Influence

Political Neutrality

· Risk of Ideological Manipulation: Intelligent machines in elder care could be used to influence conversations about end-of-life decisions or resource priorities, threatening autonomy and dignity.

· Algorithmic Transparency: The EU’s AI Act classifies health-related AI as high-risk and mandates explainability—key for preventing hidden ideological coding.

· WHO Principles: WHO guidelines on ethical AI stress fairness, non-discrimination, and autonomy, especially in politically sensitive contexts.

Pharmaceutical Influence

· Commercial Interests: Algorithms for medication and treatment recommendations may be biased by pharmaceutical companies.

· Bias and Inequity: Research shows AI can exacerbate socio-economic disparities in pharma access and pricing.

· Ethical Safeguards: Independent audits, transparency about commercial ties, and informed consent are critical to maintaining trust in care relationships.

Policy Recommendations

· Establish independent oversight bodies for intelligent machines in health and pharmaceuticals, free from state and corporate influence.

· Create standardized audit protocols in line with the EU AI Act to detect political bias and commercial manipulation.

· Ensure transparency with patients and staff regarding AI system functions, data sources, and any conflicts of interest.

Conclusion

The Last Companion is not a technological utopia but a vision of dignity and co-evolution. When humans and intelligent machines develop together, elder care can become both more humane and more effective.

References

· EU AI Act – requirements for transparency and risk management.

· WHO (2025): Ethical Guidelines for AI in Healthcare.

· Biswas, I. (2025): Relational Accountability in AI-Driven Pharmaceutical Practices.

· Ngozi & McKay (2024): Bias Risks in AI-Driven Drug Manufacturing.

· Hussain (Pharmanow): Risks in Algorithmic Quality Systems in Pharma.

· Transparency Frameworks: Principles for Accountability and Explainability in Medical AI.